by Michael Eggleston* (Advanced Biofuels USA) Today it seems that the use of anaerobic digestion in the Ocean State is not as widespread as it once was. According to a recent survey conducted by the Narragansett Bay Commission (NBC), owner and operator of Rhode Island’s (RI) two largest wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs), over half of the State’s 19 WWTFs used to use anaerobic digestion. Now NBC’s digester located in Rumford, RI, is the only digester that’s still in operation. This is surprising because anaerobic digestion is able to reduce the volume of sewage sludge disposal in half, sludge which is mostly incinerated nowadays.

NBC’s Bucklin Point municipal wastewater sludge digester in Rumford, RI

NBC’s Bucklin Point municipal wastewater sludge digester in Rumford, RIPhoto: Courtesy of B. Wenskowicz, Narragansett Bay Commission

As for the resulting biogas, about half is burned to heat the digesters while the rest is flared off. Later this year, however, the NBC plans to commission a new combined heat and power (CHP) generator system fueled predominately by their anaerobic digester biogas, the first of its kind in RI to utilize sewage sludge.

Biogas in RI

Natural gas, a non-renewable fossil fuel, contributes a lion’s share of the State’s net electric generation. According to the Energy Information Agency (EIA), natural gas fueled about 92 percent of RI's net electric generation in 2017. Biogas, on the other hand, is a source of renewable energy that can replace natural gas.

Instead of being derived from non-renewable resources, biogas is created by the anaerobic digestion of biogenic material. RI ranks #47 among United States (US) states in its biogas potential. According to the American Biogas Council, wastewater is the most underutilized biogas resource in the State. These resources, however, are estimated to contribute to only less than a fraction of a percent of the State’s net electric generation, relative to 2017; assuming a capacity factor of 67% (sample calculations are provided in Appendix 2).

Biogas produced by the anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge is often flared off as waste Photo: Courtesy of B. Wenskowicz, Narragansett Bay Commission

Biogas produced by the anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge is often flared off as waste Photo: Courtesy of B. Wenskowicz, Narragansett Bay Commission

Although biogas sourced from wastewater is not projected to become a significant contributor of renewable electricity generation in RI itself, it does represent an already distributed and dispatchable source of energy for WWTFs themselves. The National Biosolids Partnership reports that there is a growing awareness that wastewater treatment plants are not waste disposal facilities, rather they are water resource recovery facilities that produce clean water, recover nutrients, and have the potential to reduce the nation’s dependence on fossil fuel through the production and use of renewable energy.

In the past few years, RI has seen other types of renewable gas powered generation installed. An anaerobic digester for food waste was initially commissioned next to RI’s Central landfill in 2017. Although the Blue Sphere anaerobic digester doesn’t use any sludge from municipal wastewater treatment operations, it does include an anaerobic digester, biogas clean-up system, wastewater treatment system for nitrogen removal and internal reciprocating engines. Considering that the project costed $18.9 million in 2015 with a total capacity near 3,000 kW, this article will explore whether a project of this type that processed municipal wastewater sludge would represent an efficient way to utilize renewable energy coming from a host of WWTFs in the region.

Overview

The purpose of this article is to assess the financial feasibility of installing at WWTFs the “workhorse” behind this proposition, namely a reciprocating internal combustion (IC) CHP generator. IC-CHP generators are a widespread and well-known technology, which typically range in size from 30 kW to 250 MW. This centralized generator itself is estimated to have a nameplate capacity of 3,368 kW; a figure based on the 16 individual biogas systems cited by the ABC capable of capturing RI’s underutilized wastewater resources and a flow analysis conducted by the NBC.

Understanding the effects of renewable energy sources requires quantitative analysis. Therefore, a preliminary assessment will be evaluated using an available spreadsheet tool that was prescribed by a course I took in Sustainable Energy: Economics, Environment & Policy taught by Dr. James Opaluch at the University of Rhode Island. Namely, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL) Cost of Renewable Energy Spreadsheet Tool (CREST) for anaerobic digestion will serve as a means to compare the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of this centralized project to that of RI’s current commercial electricity market price.

Finally, policy recommendations regarding the implementation of a federal biogas policy to incentivize installation of these systems for multifaceted use will also be proposed. This pertains to using biogas primarily as a resource to supply renewable electricity for electric vehicle (EV) power consumption.

An Analytical Approach – NREL Spreadsheet Tools

Spreadsheet-based tools are helpful to assess many different scenarios for renewable energy facilities quickly and at a low cost. These tools are generally not intended as a substitute for detailed project-analysis, rather, they are intended as screening tools aimed at determining whether or not these projects are of interest for development.

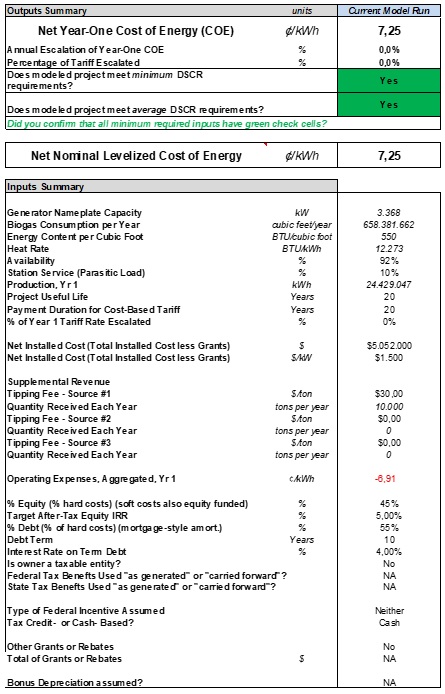

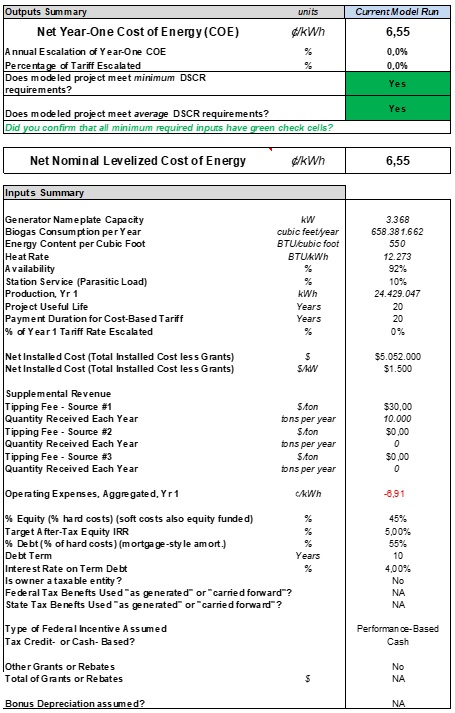

Since CREST is intended as a screening tool, a few assumptions were made utilizing the software’s “simple” input model. Performance, cost, and operating inputs were assumed to be at default value except for an electrical conversion efficiency of 27.8%, installed cost of $1,500/kW, variable operations and maintenance (O&M) expense of 2.5 ¢/kWh, and a minimum initial debt term of 10 years. The proprietor of such a generator is assumed to most likely be a public entity, therefore the minimum interest rate on term debt of 4%, and target after-tax equity internal rate of return (IRR) of 5% were applied. All spreadsheet inputs may be reviewed in Tables 1 and 2 which are provided in Appendix 3.

CREST Results & Suggestions for Future Analysis

Compared to the average price of commercial electricity in RI of 18.01 cents/kWh, the LCOE of a centralized powered IC-CHP generator is nearly two-thirds less considering CREST’s standard data for Performance-Based Cash Standard Federal Incentives (Table 2). In comparison to no federal incentives (Table 1), the cost is about 60% less. In both cases the first year’s operating expenses are estimated to comprise nearly all or more of the projected LCOE; a project projected to cost about $5.05 million (net installed cost).

The positive benefits of developing diverse renewable energy resources are well known locally. The RI Renewable Energy Growth (REG) Program incentives new renewable power projects by offering a fixed feed-in-tariff (FIT) above the market cost of electricity. Currently the FIT for anaerobic digester projects is 20.85 cents/kWh for projects from 1 – 5,000 kW in nameplate capacity with the goal of installing 1 MW of anaerobic digestion capacity per annum. REG conducts a comprehensive CREST analysis yearly in order to update the ceiling prices for new anaerobic digestion, as well as wind, solar and hydropower projects. Although REG aims to develop FITs equitably, the NBC suggests that wind and solar FITs are utilized vastly more than anaerobic digestion FITs.

Since the proprietor of the only generator of this type is a non-profit public corporation and cannot utilize tax incentives, the NBC suggests that low interest capital may be available through the State Revolving Loan Program or the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank for eligible public projects. Alternately, net-metered projects could choose to apply for a partial grant from the RI Renewable Energy Fund and financial incentives from an energy efficiency fund are also available for those who net-meter. This allows the project owner to maintain ownership of Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) unlike the alternative REG program. In those regards, a WWTF may likely choose to export all renewable power so that they can get an attractive FIT price for the entire net amount of electricity produced and exported respectively.

Hypothetically, the addition of a “centralized” anaerobic digester could be installed at a WWTF that already has a sewage sludge incinerator. That way, any digested sludge that couldn’t be used could possibly be incinerated as a last option, permit permitting. One drawback to this proposal, however, is that the host WWTF may not welcome the extra nitrogen that comes out of any digester, but would likely welcome the financial benefits produced by a centralized form of generation.

Moving forward, conducting further research into determining the cost of a centralized anaerobic digester and subsequent biogas clean up system would help develop a more comprehensive understanding of the CREST-LCOE results; along with an investigation into more complex inputs such as capital, operating, maintenance and non-monetizable costs i.e. refining the IRR, tipping fees and revenue from RECs.

NBC’s municipal wastewater sludge digester-powered CHP generator

NBC’s municipal wastewater sludge digester-powered CHP generatorPhoto: Courtesy of B. Wenskowicz, Narragansett Bay Commission

Leading by Example

In a recent interview I conducted with NBC’s Environmental Sustainability Engineer, Barry Wenskowicz, he disclosed that avoiding the cost of electricity and creating revenue from the sale RECs were financial benefits considered for the new project. The new system is being integrated into the existing sewage sludge digester that has operated at its Bucklin Point’s WWTF since 1952.

The system is expected to power a third of their Bucklin Point operations, the equivalent amount of power used by 767 typical RI households. At the heart of the new system is a 644 kW gross electric output (at a power factor of 1) reciprocating engine-generator set coupled by a new biogas clean-up system. The engine was manufactured by Guascor which is now part of Dresser Rand. The system was designed by Brown & Caldwell and was installed by BioSpark. Although the nameplate capacity is relatively small, the system is expected to be able to run around the clock unlike weather-dependent wind and solar powered generators. The new CHP plant also has the ability to burn natural gas or a blend if needed.

A new biogas clean-up system prior to the engine helps protect downstream equipment and maximize the amount of heat and power that will be recovered. It removes water using a chiller and uses non-impregnated activated carbon to remove hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and siloxane gases. Removing H2S helps protect downstream equipment from corrosion and helps avoid the formation of sulfur dioxide, a regulated air pollutant. Removing siloxanes protects downstream equipment by keeping out silica; which is known to impact air pollution control equipment, heat exchangers and engines. This is also a key change in practice that is expected to improve the heat recovery efficiency, Wenskowicz mentioned. The complete system which includes filter beds, blowers, chiller, engine compartment, radiators (used only when needed) can be seen in the picture below.

Wenskowicz added that the CHP project proved to be a substantial investment, providing 6 years of profit succeeding its 14-year payback period. However, replacing it won’t cost nearly as much, because all the associated infrastructure will already be in place. Non-monetized incentives were also considered by NBC, an environmental agency, in the decision to move forward with the project.

The NBC has been open to the idea of utilizing excess biogas for transportation fuel under the federal Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) since Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) are more valuable than RECs per unit energy. However, once the new project is fully operational they don’t expect to produce biogas beyond what is needed for the CHP. That could change if sludge pretreatment or co-digestion was ever started to boost biogas production at the facility in the future. Based on past talks with the local natural gas supply utility, carbon dioxide (CO2) would also need to be removed from the biogas prior to injection into their local pipeline; cleaned biogas will currently contain about 40% biogenic CO2. The added costs to boost production and further clean-up the biogas make it less likely that NBC will utilize RINs in the near future.

RI’s Executive Order 15-17 requires all state agencies to procure 100% of their electricity from renewable resources by 2025 subject to funding constraints. Although NBC is a Quasi-State Agency, their goal is to also power operations where economically beneficial via sustainable energy within the coming years; currently procuring about 60% to 80% of its electricity from new local sustainable sources of power (all RECs currently sold), thus affirming their reputation as a recognized environmental and energy leader.

Wenskowicz noted that the NBC will continue to own the majority of its generating capacity and contract for the balance using Public Entity Net-Metering Financing Arrangements as allowed by RI legislation.

Isn’t biogas already clean?

Instead of using biogas for on-site use, it can be “upgraded” into renewable natural gas (RNG) using an intensive purification process which creates a comparable handling quality to that of fossil natural gas. Once upgraded, RNG can either be liquefied or compressed into a transportation fuel on-site, or integrated into the natural gas grid via compression to be distributed to off-site locations. Hereby, RNG may be used to produce electricity or become transformed into a transportation fuel. Liquefaction can also be employed to transport RNG overseas via tankers.

According to the US Department of Energy (DOE), natural gas accounts for about two-tenths of 1% of all transportation fuel in the US. Two forms of natural gas can be used as transportation fuel, namely, compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG). LNG is suitable for heavy- and medium-modes of transportation because liquid is denser than gas, and therefore, more energy can be stored by volume whereas, CNG is typically used in lighter-duty vehicles. Compared to LNG however, CNG is more cost-effective due to the fuel’s widespread use in commercial applications, according to the DOE.

When biogas is only used for heat or on-site electricity production, however, only water, H2S, and siloxane removal is required. Upgrading to RNG requires the additional removal of CO2; ABC has an excellent flow chart that illustrates the RNG Upgrade Processing Pathway.

Out of all of these technologies, only activated carbon, as in NBC’s case, is cited by the ABC to remove both H2S and siloxanes from biogas. The proper design of the clean-up system helps ensure that bed life will be maximized and carbon replacement costs minimized. Spent carbon must be properly managed which may include regeneration or proper disposal.

After impurity removal, biogas is either sent to an on-site CHP unit for immediate use, like in NBC’s case, or it can be further purified to become RNG for sale as a transportation fuel or integration within the natural gas grid via CO2 removal techniques such as membrane separation, liquefaction or pressure swing adsorption (PSA).

Whilst membrane separation offers moderate energy requirements, complex multistage configurations and expensive filters are required in order to ensure high removal rates. Another option, liquefaction, enables the immediate transformation of biogas into a renewable fuel or for overseas shipment. Due to the high costs of liquefaction technologies, their use is generally recommended for large scale applications only. On the other hand, PSA generally has lower capital costs, however, its low CO2 removal rate is cited as being uncompetitive to other technologies on the market. To this end, considering RINs for producers such as the NBC affirms their decision to continue to sell RECs in the near future as there is no excess biogas to incentivize CO2 removal.

Biogas for EVs?

Established by Congress in 2005 in the Energy Policy Act and expanded and extended by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, the RFS promotes transitioning US transportation fuels from fossil-based to renewables such as biogas derived from municipal wastewater sludge digesters. Compliance is tracked via RINs.

The EIA considers renewable CNG derived from D3 RINs to be the most successful cellulosic biofuel pathway to date. Cellulosic biofuels are defined by the programs administrator, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to be renewable sources of biomass that are able to meet at least a 60% greenhouse gas “lifecycle” reduction. This is important to note when considering issues regarding the implementation of the RFS because the cellulosic biofuel renewable volume obligation (RVO) established by the EPA has yet to be met, thus fostering doubt as to its value in the eyes of some decision makers who want to amend or even repeal the RFS. The Congressional Research Service recently prepared an assessment of that highlights these issues in more detail for members and committees of Congress.

If electricity produced by biogas can be matched with corresponding amounts of electricity consumed by EVs on a physically connected electric grid, valuable credits, or "eRINs," can be generated and sold in accordance with the RFS program. Authorized by Congress in 2007 and approved as a pathway in 2014, the EPA has yet to register facilities and recognize eRINs for electricity producers. In the words of Bob Cleaves, President of the Biomass Power Association, “this is a simple case of an agency refusing to undertake what lawyers call nondiscretionary duty. The effects of the EPA’s failure to act are significant. All of our industries are experiencing closures. It’s not up to the EPA to pick and choose which transportation fuels to make part of the RVO. Congress already made that decision.”

What has stalled the EPA is the unresolved issue pertaining to eRIN credit ownership. The EPA is hung up on ensuring that there is no double counting or fraud between EV manufacturers, utilities generating the power, or the charging stations contracting for the electricity, clarified Cleaves. Cleaves explained that EPA can either recognize contracts between RNG providers, power producers, and end users, just as EPA does when administering the RNG program in the RFS for direct transportation fuels; or every producer shares “a split of the pot”. Cleaves adds that everyone who produces power qualified under a “split the pot” program would be registered in the EPA database and then EPA would calculate how much power EVs consume and distribute a fractional eRIN to everyone who contributed. Many people have been frustrated by EPA’s inability to act quickly on the pathway, but it isn’t a simple issue, Cleaves pointed out. “Once this pathway is implemented, it will be approaching 50 percent of the D3 RIN market, so it’s a very significant programmatic issue and not just a niche, one-off issue,” he disclosed. Cleaves added that every Senate and House member who has a biomass or biogas plant in their state is aware of the eRIN issue. He urges biomass power producers to write their representatives in stating, “Congress is most effective when they hear from people who vote them in and out of office, and this is a perfect example of that.”

Recently, a bipartisan group of 21 members of Congress, led by Rep. John Shimkus (R-IL) and Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-ME), sent a letter urging the EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler to “expeditiously review and approve worthy pending applications to produce RFS-certifies fuels, permitting them to proceed to market.” The letter specifically highlighted the contributions of electricity from biomass, biogas and other qualifying forms of renewable energy to rural economies, and the need to include these and other pathways in the RFS “to allow approved pathways the market access that Congress intended them to have.” The following week a bipartisan group of 9 Senators, led by Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) and Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR), also sent a letter to EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler urging action to activate eRINs. These letters follow a provision in the Interior-EPA Appropriations bill signed by President Trump earlier in February 2019 that “strongly encouraged” the EPA to process applications from electricity producers to participate in the RFS.

About 104 million eRINs could be generated from on-road EVs and plug-in-hybrid electric vehicles, a $219 million market at 9 cents per kWh projected by Chief Marketing Officer at Element Markets, Randy Lack. This doesn’t take into account municipal fleets, which could account for an additional 300-million-plus kWh, and 13.3 million more D3 RINs valued at nearly $28 million, or $2.10 per D3 RIN, he added. Lack suggests that it is easy to project that this could be a $400 million to $500 million market by 2020, depending on the volatile price of RINs. The question that remains for the EPA is how EV load development will be factored into RVOs, he disclosed.

Leading the front to activate the eRIN pathway of the RFS is the RFS Power Coalition. Around the same time of the aforementioned congressional efforts, representatives from the coalition met with the US Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to advocate for the regulatory review of the pathway’s business impact and respective federal agency coordination. The RFS Power Coalition asserted that if OIRA authorizes the currently proposed 2020 RVO, an action which is presumably silent on eRINs, then it runs the risk of retroactively imposing further obligations on RIN buyers to make up for the volume. This will, in the eyes of the coalition, send the RFS program into complete disarray and create extreme market turmoil. Moreover, the coalition has an action before the D.C. Circuit, challenging EPA’s failure to include eRINs in this year’s RVO on the grounds of promulgating an unlawful rule. “The EPA has the statutory duty to coordinate with the Secretary of Energy and the Secretary of Agriculture when promulgating the RVO. The EPA never consulted the DOE on the amount of electricity used for transportation, but we have”, stated representatives from the coalition. Cleaves maintained that his organization, one of the founding associations of the coalition, will continue to pursue their case until they are successful. Cleaves encourages all companies who are associated with the biogas industry to contact him directly, if they are interested in getting involved with the RFS Power Coalition.

Conclusion & Policy Recommendations

If RI is to move towards a “sustainable” future for its electricity generation it must look towards renewable solutions that can assist the state in mitigating its near “complete” reliance on natural gas. The State’s biogas potential is relatively minor compared to statewide electricity generation, even if co-digestion were to be widely adopted to boost biogas production from wastewater resources.

On the other hand, biogas sourced from WWTFs themselves represents an already distributed and dispatchable source of energy. The benefits of coupling a municipal wastewater sludge digester to a CHP generator creates value two-fold, whereby the reduction in expense of sewage sludge disposal from the digester itself is complemented by powering a portion of municipal operations.

Therefore, a more comprehensive CREST analysis is encouraged in order to determine why wind and solar FITs are much more utilized than anaerobic digestion FITs administered by RI’s REG Program. Special attention should be drawn to Blue Sphere’s anaerobic digester in Johnston, RI when considering a centralized wastewater digester project, despite its drawbacks in having to pay for the handling extra nitrogen concentrations. Further research into the cost of a centralized digester installation and subsequent biogas clean up system, including alternative financial incentives and more complex financial inputs, will provide a clearer understanding of the CREST-LCOE result. Tools such as NREL’s Jobs and Economic Development Impact (JEDI) Model are also encouraged to be used in order to assess the local economic impact of projects of this magnitude.

If eRINs continue to be stalled by the EPA, however, it is highly unlikely that WWTF biogas producers will be able to expand production capacity, especially considering that no excess biogas is expected from NBC’s new system. In order to resolve the “eRIN dilemma”, President of the Biomass Power Association, Bob Cleaves, suggests that every contributor throughout the value-chain should be registered by the EPA and rewarded accordingly to ensure no double-counting or fraud occurs amongst producers. Moreover, the emergence of the RFS Power Coalition has marked an age in the waste-to-energy industry that has come to bring justice to renewable, domestically sourced, carbon-friendly technology that has struggled to gain foothold without the benefit of federal subsidies.

In terms of upgrading biogas for multifaceted use as a transportation fuel or integration into the natural gas grid, producers must consider the incremental costs related to the quality of their biogas, including the proper management of activated carbon and implementing expensive equipment for the removal of CO2. If incentives were available to install sludge pretreatment or co-digestion capable of boosting biogas production in the future, the NBC states that they would need to reconsider the opportunity cost of expanding its engine driven capacity or venture into RNG production.

Although coal-fired electricity generation in the US has fallen by about a third since 2009, natural gas had relatively filled the gap in 2017, up by about 41 percent in the same time frame. More broadly speaking, natural gas has played an integral role in the electric utility sector by lowering electricity costs, and reducing carbon emissions. The Union of Concerned Scientists suggests, however, that overly relying on natural gas in the electric sector, especially to fuel demand of EV growth, could be a problem. Therefore, biogas sourced from local underutilized resources must be given greater attention.

The biogas industry complements rural America by enabling farmers to cost-effectively and sustainably convert waste to energy. Biogas also provides an opportunity that not many other renewable energy technologies can compete with. By maintaining a constant flow of sustainable electricity, fuel, and a slew of other bio-based products, now, more than ever, is the time to consider investing in the country’s future with biogas.

*Michael Eggleston is a Volunteer Renewable Fuels Correspondent and Research Associate for Advanced Biofuels USA. Presently, he is responsible for updating the organization’s white paper on the differences between biodiesel and renewable (green) diesel. Michael is employed by VERBIO North America Corporation (VNA) as an Engineering Intern at their Nevada Biorefinery, former site of DuPont’s 30 MGPY cellulosic ethanol facility. Opinions in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of VNA.

Appendix

1. Abbreviations

Carbon dioxide (CO2)

Combined heat and power (CHP)

Compressed natural gas (CNG)

Cost of Renewable Energy Spreadsheet Tool (CREST)

Department of Energy (DOE)

Electric vehicle (EV)

Energy Information Agency (EIA)

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Feed-in-tariff (FIT)

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)

Internal combustion (IC)

Internal rate of return (IRR)

Jobs and Economic Development Impact (JEDI)

Levelized cost of energy (LCOE)

Liquefied natural gas (LNG)

Narragansett Bay Commission (NBC)

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA)

Operations and maintenance (O&M)

Pressure swing adsorption (PSA)

Renewable Energy Credits (RECs)

Renewable Energy Growth (REG)

Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS)

Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs)

Renewable natural gas (RNG)

Renewable volume obligation (RVO)

Rhode Island (RI)

United States (US)

VERBIO North America Corporation (VNA)

Wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs)

2. Sample Calculations

Centralized Digester Nameplate Capacity = (4,000 kW/19 WWTFs in RI)*16 estimated plants = 3368.4 kW

Centralized Digester Net Electricity Generation = [3368.4 kW*0.67*365 days/year]*(1GWh/1,000,000 kWh) = 0.824 GWh

Centralized Digester Contribution to Electricity Generation relative to 2017 = (0.824 GWh/7,614.94 GWh)*100% = 0.011%

CREST Incentive Impact = (|6.55-18.01|/18.01)*100% = 66.63%

CREST Comparison to RI LCOE = (|7.25-18.01|/18.01)*100% = 59.74%

Natural Gas Electricity Share 2017 = (1,296,415 MWh/4,034,268 MWh)*100% = 32.14%

Natural Gas Use Increase relative to 2009 = [(1,296,415 -920,979 thousand MWh)/(920,979 thousand MWh)]*100% = 40.76%

Coal Use Decrease relative to 2009 = [(1,755,904 – 1,205,835 MWh)/(1,755,904 thousand MWh)]*100% = 31.32%

3. CREST Data

Table 1: CREST Summary No Standard Federal Incentives

Table 2: CREST Summary for Performance-Based Cash Standard Federal Incentives

Anaergia acquires Rhode Island anaerobic digestion facility (Biomass Magazine)

Nearly 55,000 articles in our online library!

Use the categories and tags listed below to access the nearly 50,000 articles indexed on this website.

Advanced Biofuels USA Policy Statements and Handouts!

- For Kids: Carbon Cycle Puzzle Page

- Why Ethanol? Why E85?

- Just A Minute 3-5 Minute Educational Videos

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- “Disappearing” Carbon Tax for Non-Renewable Fuels

- What’s the Difference between Biodiesel and Renewable (Green) Diesel? 2020 revision

- How to De-Fossilize Your Fleet: Suggestions for Fleet Managers Working on Sustainability Programs

- New Engine Technologies Could Produce Similar Mileage for All Ethanol Fuel Mixtures

- Action Plan for a Sustainable Advanced Biofuel Economy

- The Interaction of the Clean Air Act, California’s CAA Waiver, Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards, Renewable Fuel Standards and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard

- Latest Data on Fuel Mileage and GHG Benefits of E30

- What Can I Do?

Donate

DonateARCHIVES

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- June 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- October 2006

- April 2006

- January 2006

- April 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- December 1987

CATEGORIES

- About Us

- Advanced Biofuels Call to Action

- Aviation Fuel/Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

- BioChemicals/Renewable Chemicals

- BioRefineries/Renewable Fuel Production

- Business News/Analysis

- Cooking Fuel

- Education

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- Competitions, Contests

- Earth Day 2021

- Earth Day 2022

- Earth Day 2023

- Earth Day 2024

- Earth Day 2025

- Executive Training

- Featured Study Programs

- Instagram TikTok Short Videos

- Internships

- Just a Minute

- K-12 Activities

- Mechanics training

- Online Courses

- Podcasts

- Scholarships/Fellowships

- Teacher Resources

- Technical Training

- Technician Training

- University/College Programs

- Events

- Coming Events

- Completed Events

- More Coming Events

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters Completed

- Webinars/Online

- Webinars/Online Completed; often available on-demand

- Federal Agency/Executive Branch

- Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Agriculture (USDA)

- Commerce Department

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- Congressional Budget Office

- Defense (DOD)

- Air Force

- Army

- DARPA (Defense Advance Research Projects Agency)

- Defense Logistics Agency

- Marines

- Navy

- Education Department

- Energy (DOE)

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

- Federal Reserve System

- Federal Trade Commission

- Food and Drug Administration

- General Services Administration

- Government Accountability Office (GAO)

- Health and Human Services (HHS)

- Homeland Security

- Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

- Interior Department

- International Trade Commission

- Joint Office of Energy and Transportation

- Justice (DOJ)

- Labor Department

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- National Research Council

- National Science Foundation

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation

- Patent and Trademark Office

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- State Department

- Surface Transportation Board

- Transportation (DOT)

- Federal Aviation Administration

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Admin (PHMSA)

- Treasury Department

- U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

- White House

- Federal Legislation

- Federal Litigation

- Federal Regulation

- Feedstocks

- Agriculture/Food Processing Residues nonfield crop

- Alcohol/Ethanol/Isobutanol

- Algae/Other Aquatic Organisms/Seaweed

- Atmosphere

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

- Field/Orchard/Plantation Crops/Residues

- Forestry/Wood/Residues/Waste

- hydrogen

- Manure

- Methane/Biogas

- methanol/bio-/renewable methanol

- Not Agriculture

- RFNBO (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin)

- Seawater

- Sugars

- water

- Funding/Financing/Investing

- grants

- Green Jobs

- Green Racing

- Health Concerns/Benefits

- Heating Oil/Fuel

- History of Advanced Biofuels

- Infrastructure

- Aggregation

- Biofuels Engine Design

- Biorefinery/Fuel Production Infrastructure

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- certification

- Deliver Dispense

- Farming/Growing

- Precursors/Biointermediates

- Preprocessing

- Pretreatment

- Terminals Transport Pipelines

- International

- Abu Dhabi

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Albania

- Algeria

- Angola

- Antarctica

- Arctic

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Aruba

- Asia

- Asia Pacific

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bahamas

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Barbados

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Belize

- Benin

- Bermuda

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Botswana

- Brazil

- Brunei

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Caribbean

- Central African Republic

- Central America

- Chad

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Congo

- Congo, Democratic Republic of

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Dubai

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eqypt

- Estonia

- Eswatini/Swaziland

- Ethiopia

- European Union (EU)

- Fiji

- Finland

- France

- French Guiana

- Gabon

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Global South

- Greece

- Greenland

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Guinea

- Guyana

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Ivory Coast

- Jamaica

- Japan

- Jersey

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Korea

- Kosovo

- Kuwait

- Laos

- Latin America

- Latvia

- Lebanon

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macedonia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mali

- Malta

- Marshall Islands

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Mexico

- Middle East

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Mongolia

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Myanmar/Burma

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Netherlands

- New Guinea

- New Zealand

- Nicaragua

- Niger

- Nigeria

- North Africa

- North America

- North Korea

- Northern Ireland

- Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Panama

- Papua New Guinea

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Republic of

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Scotland

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Sierra Leone

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South America

- South Korea

- South Sudan

- Southeast Asia

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Suriname

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Timor-Leste

- Togo

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- UK (United Kingdom)

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates UAE

- Uruguay

- Uzbekistan

- Vatican

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Wales

- Zambia

- Zanzibar

- Zimbabwe

- Marine/Boat Bio and Renewable Fuel/MGO/MDO/SMF

- Marketing/Market Forces and Sales

- Opinions

- Organizations

- Original Writing, Opinions Advanced Biofuels USA

- Policy

- Presentations

- Biofuels Digest Conferences

- DOE Conferences

- Bioeconomy 2017

- Bioenergy2015

- Biomass2008

- Biomass2009

- Biomass2010

- Biomass2011

- Biomass2012

- Biomass2013

- Biomass2014

- DOE Project Peer Review

- Other Conferences/Events

- R & D Focus

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- Co-Products

- Feedstock

- Logistics

- Performance

- Process

- Vehicle/Engine/Motor/Aircraft/Boiler

- Yeast

- Railroad/Train/Locomotive Fuel

- Resources

- Books Web Sites etc

- Business

- Definition of Advanced Biofuels

- Find Stuff

- Government Resources

- Scientific Resources

- Technical Resources

- Tools/Decision-Making

- Rocket/Missile Fuel

- Sponsors

- States

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawai'i

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Midwest

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Native American tribal nation lands

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington DC

- West Coast

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

- Sustainability

- Uncategorized

- What You Can Do

tags

© 2008-2023 Copyright Advanced BioFuels USA. All Rights reserved.

.jpg)

Comments are closed.