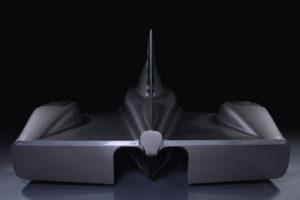

Not only do they look like 5th generation fighter aircraft and hit speeds of over 230 mph, but they do it with small turbocharged 4-cylinder engines, similar to the ones in the Ford Focus. They get great mileage from 2nd generation biofuels and their fuselages (isn't that the term for airplanes?) are built from bioplastics that are also recyclable.

On top of all that, these "DeltaWing" racers cost ½ as much as their slower, more inefficient predecessors.

For some long-time race fans, it's been hard to adjust eyes that were used to seeing the same winged creations race since the middle 1970s.

But new fans were not encumbered with these preconceptions. Instead little kids wanted Hot WheelsTM versions of these cars that look like the ones they draw on their computers while not doing schoolwork. NASCAR fans found themselves drawn to the speed and the flat out novelty of these new cars. (Admittedly some were becoming hardcore Danica fans.) In addition, because the DeltaWing cars used "open architecture" small underfunded teams were suddenly competitive. This made for great stories on all forms of media which attracted fans of other sports who loved rooting for underdogs.

Even more surprising was another contingent of new fans. These people found the sport when they heard about these Green cars and how techie the Indy 500 had suddenly become. Recycled bioplastics, open source architecture, and low-impact 2nd generation biofuels getting up to 20 mpg at 200 mph? They tuned in and found something they didn't know they liked. They could enjoy the speed, competition, drivers, and excitement without feeling guilty about Carbon Footprints. And, if these technologies were being developed at Indy, when would they be available in road cars? When would lightweight, very safe, and very efficient vehicles be ready for sale?

Now you're probably asking, would this scenario ever happen or is it just the pipedream of some biofueled technofreak?

The DeltaWing Project

At the Chicago Auto Show in early February 2010, the concept race car pictured above was introduced as the DeltaWing Racer by a group of leading Indy racing teams. Working together as Deltawing Racing Cars LLC, the DeltaWing Racer is being promoted as a complete paradigm change in open-wheel racing. Their goal is stated as:

"Half the power, half the weight, half the drag, half the cost, half the fuel, but still the same high speed."

In their presentation and press releases (www.deltawingracing.com) they use terms like: sustainability, environmentally responsible, responding to the rising cost of energy, and relevance to more than the racing audience.

The DeltaWing group also talks about realignment with the automobile industry and making Indy Car racing a showcase for American design and engineering excellence, much as it had been from its inception in 1911 until about the mid 1990s.

So, how much of this is hype and greenwashing and how much is reality? I've been looking at their website, reading articles and interviews of the principles involved and exchanging e-mails to try to get a handle on this. So here goes.

It Will Happen, and the BioFuel and BioProduct Community Should Be a Part of It

My personal opinion is that the 2012 switch to the DeltaWing, or something very close to it will happen. My other opinion is that after a slow start, this emphasis on energy efficiency and new bio-based technologies will be common to all forms of car racing, even NASCAR.

Here are my four reasons why DeltaWing will bring fans and success back to Indy car racing and offer an important technological and marketing platform for biofuels and bioproducts.

First, the team owners behind DeltaWing acknowledge that the sport is in financial trouble. Even before the economy collapsed in 2008 auto racing of all types, and especially Indy car were losing fans and sponsorship money. The Indianapolis 500 used to be the premiere motorsports event in the US. Stars like Clark Gable and Paul Newman made movies about it. (Now its NASCAR's "Talladega Nights," a great movie by the way.) But, helped along by warring sanctioning bodies, a lack of American drivers, and a stagnant vehicle design, Indy car racing became irrelevant to all but a very small, and aging, core audience.

The arrival of Danica Patrick in 2005 revived the sport somewhat and added a younger and more female audience, but without an Indianapolis 500 victory and Danica shifting her racing focus to NASCAR, "Danicamania" alone is not saving Indy.

Second, many of the key people in the sport saw that a new direction was needed to rebuild the popularity of Indy Car racing in North America. At a "green racing" seminar I attended in August 2008 in Detroit, people like 1986 Indy 500 champion and team owner Bobby Rahal stressed the importance of making racing "relevant" to the general public.

Instead of pursuing the NASCAR model which focuses on providing entertainment, Rahal and others said that the sport needed to go back to the roots of Indy car racing, which was serving as a testing ground for automotive technology, to reclaim their audience. Back to the Future as it were.

A key part of this re-integration with the automotive industry is the adoption of energy efficiency and environmental stewardship as primary goals. Currently, they are the salient technology and marketing directions of the automotive industry. Not only are improved fuel mileage technologies required to meet EPA regulations, but they are seen as important marketing drivers-witness hybrid vehicles. The DeltaWing group hopes this approach will make Indy car racing relevant and hence popular with people that currently dismiss it.

Third, and probably the most important aspect of the DeltaWing proposal, is the major reduction in costs. This reflects the reality that despite using a one-design car that is now seven years old and a relatively low-powered sole-source engine (to borrow that old advertising slogan) "Indy Car Racing Costs Too Much!" For example a one-year lease, that's right a lease not a purchase, of the sole-source medium tech Honda engine is reported to cost about $1 million dollars. The DeltaWing proposal includes potentially stock-based 2.0L 4-cylinder turbocharged engines that would last a minimum of 4,000 miles between rebuilds. Since most Indy Car races are less than 300 miles and have less than 100 miles of practice and qualifying, one engine could last up to eight or nine races. That is half the current season of seventeen races. If a number of different automobile manufacturers offer engines (listening Ford, GM, and VW?) engine prices could really drop dramatically.

If their goal of "½ the price" is met, two important tasks would be accomplished. First, it would allow existing teams to keep competing with limited funding during the rebuilding phase. This will keep a good product on the track to bring in new fans and sponsors. Second, teams with quality crews and drivers that race in lower cost racing circuits will be able to move up. This will increase qualifying competition which will lead to a higher quality racing product.

Fourth, while the looks of the DeltaWing car displayed at Chicago are highly controversial, commenters on various sites have unfavorably compared it to Speed Racer's car and the Batmobile, it reflects the reality that the next generation of Indy Car fans will be coming from the video gaming ranks. If gamers are able to race around in wild looking creations on their screens, they aren't going to pay to see dull looking cars on race tracks. For historical comparison, when the rear-engined Lotus cars, which are the basis of the current cars, appeared at Indianapolis in 1963 similar comments were made.

What DeltaWing Means for the Biofuel and BioProduct Community

I think the DeltaWing could become a significant Technological and Marketing Platform for Biofuels and BioProducts.

Fuels and Engines

Because of the light weight and low drag of the DeltaWing design, considerably less power would be needed to achieve current speeds of over 200 mph. The engine design being considered is a turbocharged 4 cylinder engine in the 2.0L range that would produce 300+ hp and last for at least 4,000 miles. This is very close to the power range of existing production engines. For example; the 2010 Mazda Speed3 (list price $24,000) uses a 2.3L 4 cylinder engine that produces 263 hp and comes with a limited 36,000 mile/3 year warranty.

There is however, one extra trick being added to this engine concept: a fuel flow rate control regulator. The idea behind this is to promote increased engine thermal efficiency and fuel mileage. The race will go to not just the fastest driver, but also the racer getting the best fuel economy.

The challenge offered by this formula of using production based engine technologies like variable timing and sequential turbocharging used in eco-boost engines, in combination with high octane and high energy content biofuels such as biobutanol should be something both engine and biofuel scienctists and engineers should welcome.

The results of these efforts would not only be exceptional racing engines but more importantly, production Multi-Fuel engines that would deliver mileage and performance well in excess of what is currently expected no matter what fuel is used.

Now, before every American ethanol producer sends me a nasty e-mail, I well know the tragedy of Paul Dana's death in 2006 at the Homestead, FL track and the bad-blood that arose between IRL (the Indy racing sanctioning body) and the Ethanol Promotion and Information Council (EPIC) that resulted in EPIC ending their contract with IRL in late 2008 and Indy Cars switching to Brazilian supplied bioethanol in 2009.

I only ask that 2nd and 3rd generation biofuel suppliers and technologists try to look forward to the breakthroughs offered by this clean-sheet approach and think of the potential the combination of new engines and new fuels offers for the future widespread use of homegrown, sustainable biofuels.

BioProducts

In an e-mail from Bill Lafontaine, Chief Marketing Officer of the DeltaWing Racing Cars, he describes the bioproducts that would be used in the crash protection structure of the car.

"We are working on a polypropylene core between carbon epoxy matrix skins replacing the conventional aluminum honeycomb core. The advantage is that we can reduce the amount of carbon very significantly and achieve not only equal energy absorption but also better anti intrusion and anti rupture in impact modes. The polypropylene is of course fully recyclable being a thermo-plastic and now the PP can be produced from bio-mass."

The US Dept. of Energy has been talking about potential markets for bioproducts for a number of years without actually putting any money into market building projects. If the DeltaWing structure were to be based primarily on biobased polymers, this could be the type of breakthrough application that could launch the bioproducts industry.

If this low-carbon, light-weight monocoque body structure could be economically transferred to production truck and car construction it could provide the weight savings needed to achieve the EPA fuel economy standards of 2020 and beyond.

Final Thoughts

I guess what excites me about the DeltaWing is that some people looked at a problem and decided to really find a solution, no matter how radical it might appear, rather than deciding to just muddle through and hope for the best. There is so much muddling through and calls for only incremental changes in both government and business that it is a blast of good clean fresh air. I hope it blasts its way through the accumulated inertia and bureaucracy of automotive racing and starts a revolution in how we can make our dreams of a high performance, energy efficient, and sustainable biobased future a reality.

Nearly 55,000 articles in our online library!

Use the categories and tags listed below to access the nearly 50,000 articles indexed on this website.

Advanced Biofuels USA Policy Statements and Handouts!

- For Kids: Carbon Cycle Puzzle Page

- Why Ethanol? Why E85?

- Just A Minute 3-5 Minute Educational Videos

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- “Disappearing” Carbon Tax for Non-Renewable Fuels

- What’s the Difference between Biodiesel and Renewable (Green) Diesel? 2020 revision

- How to De-Fossilize Your Fleet: Suggestions for Fleet Managers Working on Sustainability Programs

- New Engine Technologies Could Produce Similar Mileage for All Ethanol Fuel Mixtures

- Action Plan for a Sustainable Advanced Biofuel Economy

- The Interaction of the Clean Air Act, California’s CAA Waiver, Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards, Renewable Fuel Standards and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard

- Latest Data on Fuel Mileage and GHG Benefits of E30

- What Can I Do?

Donate

DonateARCHIVES

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- June 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- October 2006

- April 2006

- January 2006

- April 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- December 1987

CATEGORIES

- About Us

- Advanced Biofuels Call to Action

- Aviation Fuel/Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

- BioChemicals/Renewable Chemicals

- BioRefineries/Renewable Fuel Production

- Business News/Analysis

- Cooking Fuel

- Education

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- Competitions, Contests

- Earth Day 2021

- Earth Day 2022

- Earth Day 2023

- Earth Day 2024

- Earth Day 2025

- Executive Training

- Featured Study Programs

- Instagram TikTok Short Videos

- Internships

- Just a Minute

- K-12 Activities

- Mechanics training

- Online Courses

- Podcasts

- Scholarships/Fellowships

- Teacher Resources

- Technical Training

- Technician Training

- University/College Programs

- Events

- Coming Events

- Completed Events

- More Coming Events

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters Completed

- Webinars/Online

- Webinars/Online Completed; often available on-demand

- Federal Agency/Executive Branch

- Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Agriculture (USDA)

- Commerce Department

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- Congressional Budget Office

- Defense (DOD)

- Air Force

- Army

- DARPA (Defense Advance Research Projects Agency)

- Defense Logistics Agency

- Marines

- Navy

- Education Department

- Energy (DOE)

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

- Federal Reserve System

- Federal Trade Commission

- Food and Drug Administration

- General Services Administration

- Government Accountability Office (GAO)

- Health and Human Services (HHS)

- Homeland Security

- Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

- Interior Department

- International Trade Commission

- Joint Office of Energy and Transportation

- Justice (DOJ)

- Labor Department

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- National Research Council

- National Science Foundation

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation

- Patent and Trademark Office

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- State Department

- Surface Transportation Board

- Transportation (DOT)

- Federal Aviation Administration

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Admin (PHMSA)

- Treasury Department

- U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

- White House

- Federal Legislation

- Federal Litigation

- Federal Regulation

- Feedstocks

- Agriculture/Food Processing Residues nonfield crop

- Alcohol/Ethanol/Isobutanol

- Algae/Other Aquatic Organisms/Seaweed

- Atmosphere

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

- Field/Orchard/Plantation Crops/Residues

- Forestry/Wood/Residues/Waste

- hydrogen

- Manure

- Methane/Biogas

- methanol/bio-/renewable methanol

- Not Agriculture

- RFNBO (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin)

- Seawater

- Sugars

- water

- Funding/Financing/Investing

- grants

- Green Jobs

- Green Racing

- Health Concerns/Benefits

- Heating Oil/Fuel

- History of Advanced Biofuels

- Infrastructure

- Aggregation

- Biofuels Engine Design

- Biorefinery/Fuel Production Infrastructure

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- certification

- Deliver Dispense

- Farming/Growing

- Precursors/Biointermediates

- Preprocessing

- Pretreatment

- Terminals Transport Pipelines

- International

- Abu Dhabi

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Albania

- Algeria

- Angola

- Antarctica

- Arctic

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Aruba

- Asia

- Asia Pacific

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bahamas

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Barbados

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Belize

- Benin

- Bermuda

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Botswana

- Brazil

- Brunei

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Caribbean

- Central African Republic

- Central America

- Chad

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Congo

- Congo, Democratic Republic of

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Dubai

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eqypt

- Estonia

- Eswatini/Swaziland

- Ethiopia

- European Union (EU)

- Fiji

- Finland

- France

- French Guiana

- Gabon

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Global South

- Greece

- Greenland

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Guinea

- Guyana

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Ivory Coast

- Jamaica

- Japan

- Jersey

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Korea

- Kosovo

- Kuwait

- Laos

- Latin America

- Latvia

- Lebanon

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macedonia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mali

- Malta

- Marshall Islands

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Mexico

- Middle East

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Mongolia

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Myanmar/Burma

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Netherlands

- New Guinea

- New Zealand

- Nicaragua

- Niger

- Nigeria

- North Africa

- North America

- North Korea

- Northern Ireland

- Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Panama

- Papua New Guinea

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Republic of

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Scotland

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Sierra Leone

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South America

- South Korea

- South Sudan

- Southeast Asia

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Suriname

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Timor-Leste

- Togo

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- UK (United Kingdom)

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates UAE

- Uruguay

- Uzbekistan

- Vatican

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Wales

- Zambia

- Zanzibar

- Zimbabwe

- Marine/Boat Bio and Renewable Fuel/MGO/MDO/SMF

- Marketing/Market Forces and Sales

- Opinions

- Organizations

- Original Writing, Opinions Advanced Biofuels USA

- Policy

- Presentations

- Biofuels Digest Conferences

- DOE Conferences

- Bioeconomy 2017

- Bioenergy2015

- Biomass2008

- Biomass2009

- Biomass2010

- Biomass2011

- Biomass2012

- Biomass2013

- Biomass2014

- DOE Project Peer Review

- Other Conferences/Events

- R & D Focus

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- Co-Products

- Feedstock

- Logistics

- Performance

- Process

- Vehicle/Engine/Motor/Aircraft/Boiler

- Yeast

- Railroad/Train/Locomotive Fuel

- Resources

- Books Web Sites etc

- Business

- Definition of Advanced Biofuels

- Find Stuff

- Government Resources

- Scientific Resources

- Technical Resources

- Tools/Decision-Making

- Rocket/Missile Fuel

- Sponsors

- States

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawai'i

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Midwest

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Native American tribal nation lands

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington DC

- West Coast

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

- Sustainability

- Uncategorized

- What You Can Do

tags

© 2008-2023 Copyright Advanced BioFuels USA. All Rights reserved.

.jpg)

1 COMMENTS

Leave A Comment

Your Email Address wiil not be Published. Required Field Are marked*