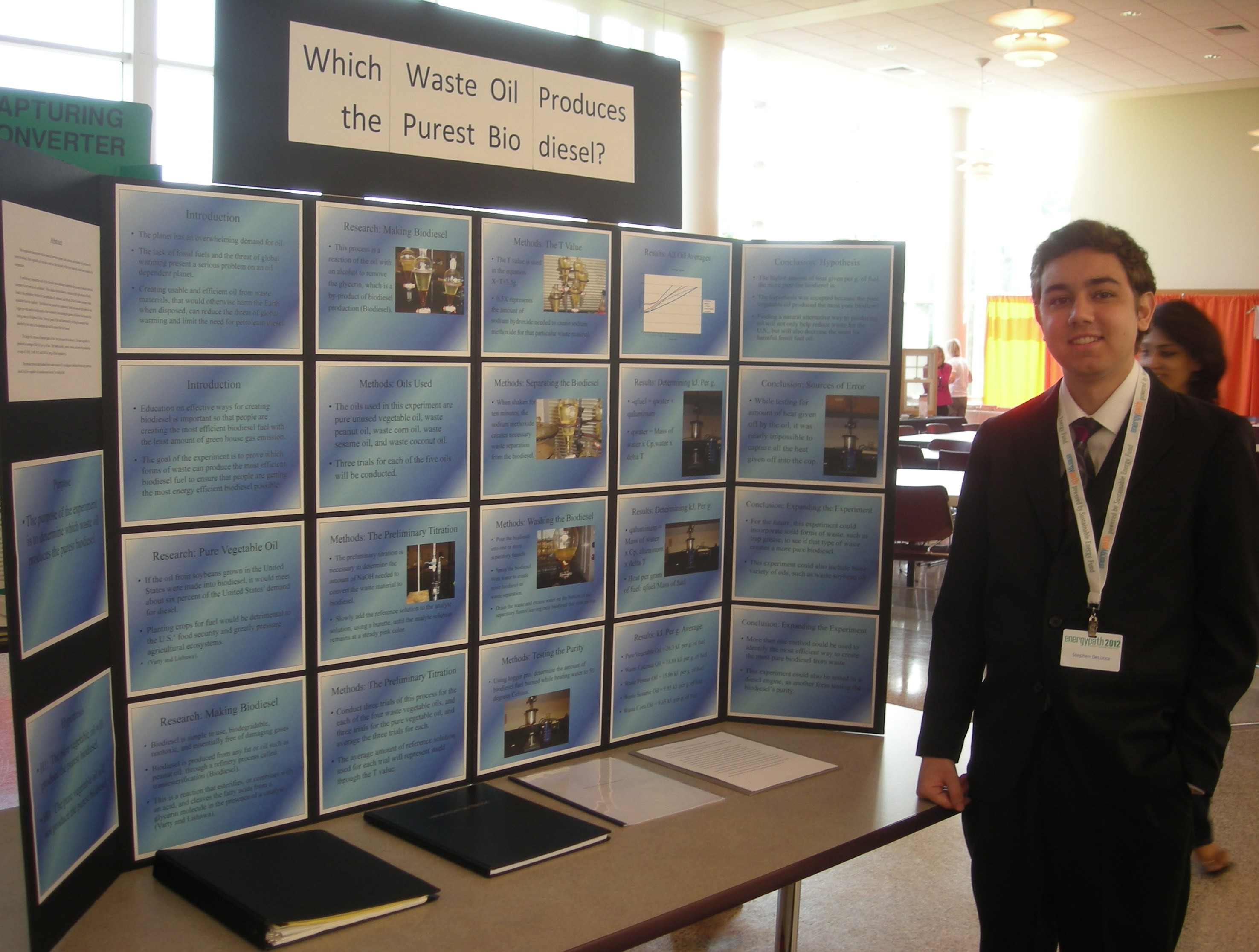

by Joanne Ivancic (Advanced Biofuels USA) He was dressed like an executive; dark suit, white shirt, tie, and struggling to get a poster board out of the back of an SUV as his mother tried to help. I glanced the word "Bio diesel" on the poster and approached the two. I offered my card to the mother, as the young man had his hands quite full, and told them Advanced Biofuels USA had an exhibit table at the EnergyPath conference, they might want to stop by or to check out our web site. I planned to stop by the poster session to see his project.

The night before the DeSales University cafeteria was re-arranged to accommodate the student science fair portion of the EnergyPath 2012 conference. I was curious to see what the students would come up with. The conference was tilted heavily toward wind and solar with some geothermal thrown in; and substantial attention to sustainability overall.

I was pleased to see four posters dedicated to biofuels-related topics. Here are their stories.

Stephen DeLucca of Fort Washington, Pennsylvania did the biodiesel research. A student at Germantown Academy starting his senior year in the fall, he said he wanted to do a chemistry project and, talking with teachers about options chose the topic, "Which Waste Oil Produces the Purest Bio diesel." I wasn't really sure from the title what he was getting at, so we had a good talk about it.

All the students in the EnergyPath Science Fair were expected to prepare a 3-10 minute speech about their projects, in addition to creating a poster board. They would meet with judges to explain their projects; and were expected to be available at their poster for a couple of hours to discuss their projects with conference attendees. In addtion, they could bring small scale tangible projects to demonstrate their research or design.

Stephen started in on his speech, but I really didn't want to hear it. I'm not a scientist and didn't care so much about the formalities. I was more intrigued by the background stories.

Stephen chose five different oils. He used pure vegetable oil (unspecified vegetable) right out of the bottle as the benchmark. He compared it to four waste oils that he created by frying potatoes in the various oils (coconut, peanut, sesame and corn). I asked about the sesame oil. Pretty expensive. His teacher contributed his supply. We discussed his choice not to use palm oil. He didn't know to think about it. He didn't know about the role that palm oil plays in the world biodiesel market. Such knowledge might have influenced his choice of oils.

That lead to us to talking about the controversies surrounding feedstocks such as palm oil and, with a nod to the price of sesame oil, to the economic element in the sustainability equation.

Back to the details of the project. More than the value of his results, I believe, was the value of the process. He could describe the lab techniques that he learned and used. He learned to make biodiesel from five different oils and observed differences. He identified weaknesses of his original plan for conducting his experiment and designed innovations to address those weaknesses and to improve the quality of his results.

Also, as so often happens, mid-course corrections were needed as unforeseen consequences arose. Recognizing that the soot that built up on the vessel of water might affect his results added a new step to his process.

I enjoyed hearing his story as it capsulized in miniature the experiences I hear of advanced biofuels companies moving from bench to pilot to demo to commercial. Doing something you've never done before, not giving up, figuring it out and becoming inspired to continue.

Stephen is interning in a chemistry lab this summer and looks forward to more science classes and to a career in this field.

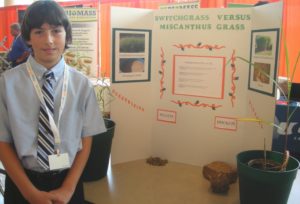

Josh Danna, a 7th grader at North Pocono Middle School in Moscow, Pennsylvania, received a lot of help from an aunt. She introduced him to miscanthus and switchgrass. His project focused on literature research comparing yields per acre and amount of fuel that could be produced per acre. He came out in favor of miscanthus over switchgrass.

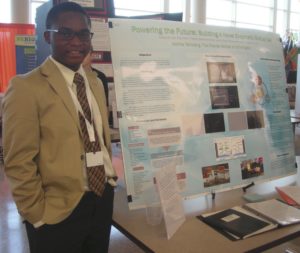

Achille Tenkiang became inspired to do research on fuel cells using renewables as a result of a trip with his parents to their home country of Cameroon when he was in the 8th grade. Now, between his junior and senior years at Charter School Wilmington, Delaware, he presented research on "Powering the Future: Building a Novel Enzymatic Biofuel Cell." Wow! Achille may be a teacher some day. This project was so over my head. It was like reading scientific articles where I know it is written in English, but beyond words like "the," "and" and "enzyme," I'm lost. Achille quite patiently walked me through, answered my questions and engaged my interest and attention. My impression was that his research was in the same ballpark as that done on fuel cells in St. Louis some years ago; research that foundered as funding diminished. I hope his work revitalizes interest in this area.

Achille said that he has been working on a biofuel fuel cell idea for three years with last year's project focused on micro-organisms rather than enzymes. I asked about his future plans. He looked a bit sheepish and said, "Yes, I should be thinking about that." He seemed more interested in actually doing research in the lab at a university five minutes from his home than doing anything else. I got the sense that he was more interested in making something real happen than getting a piece of paper indicating an academic degree.

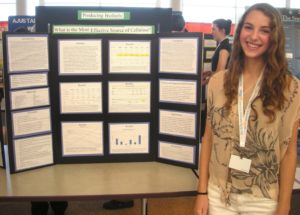

The dearth of intense plant cell research has been lamented at the Advanced Biofuels USA offices. Rachel Zuckerman of Springside Chestnut Hill Academy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania may be one to work on turning that around if she continues research in the area she showcased at EnergyPath 2012.

Her subject, "Producing Biofuels: What Is the Most Effective Source of Cellulase?" grew from her understanding that biofuels can help to mitigate the destruction of climate change. She tested four kinds of mushrooms and two molds to determine if the source of the enzymes made a difference in their effectiveness in breaking down cellulose.

The four kinds of mushrooms came from a local grocery store. She grew the two types of mold in a drawer in her refrigerator. That has got to be my favorite part. How often we joke that the leftovers hiding in the back of that vegetable bin are "science projects." At her house, it was true.

And, one of those molds beat out the other sources of cellulase significantly. Reminded me of the story of the discovery of penicillin.

Again, the journey through this project taught her lab technique and exercised her observational skills. As with the other students, her conclusion looks to the wider world and the future, "This experiment shows that there are varying efficiencies in the process of breaking down cellulose for use in fuel, so research can potentially yield an even faster process. In addition, the most effective cellulase came from mold--mold is fast, easy and cheap to grow. Therefore, it could have far-reaching implications in the world of biofuel production." There are some well-funded companies that have reached similar conclusions. Perhaps they will find Rachel in their future.

Perhaps this model of a Science Fair focused on sustainable energy will catch on. It was encouraging to see serious attention from students to understanding and developing biofuels as a solution to world-wide energy problems. READ MORE Photos by Joanne Ivancic

Nearly 55,000 articles in our online library!

Use the categories and tags listed below to access the nearly 50,000 articles indexed on this website.

Advanced Biofuels USA Policy Statements and Handouts!

- For Kids: Carbon Cycle Puzzle Page

- Why Ethanol? Why E85?

- Just A Minute 3-5 Minute Educational Videos

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- “Disappearing” Carbon Tax for Non-Renewable Fuels

- What’s the Difference between Biodiesel and Renewable (Green) Diesel? 2020 revision

- How to De-Fossilize Your Fleet: Suggestions for Fleet Managers Working on Sustainability Programs

- New Engine Technologies Could Produce Similar Mileage for All Ethanol Fuel Mixtures

- Action Plan for a Sustainable Advanced Biofuel Economy

- The Interaction of the Clean Air Act, California’s CAA Waiver, Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards, Renewable Fuel Standards and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard

- Latest Data on Fuel Mileage and GHG Benefits of E30

- What Can I Do?

Donate

DonateARCHIVES

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- June 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- October 2006

- April 2006

- January 2006

- April 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- December 1987

CATEGORIES

- About Us

- Advanced Biofuels Call to Action

- Aviation Fuel/Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF)

- BioChemicals/Renewable Chemicals

- BioRefineries/Renewable Fuel Production

- Business News/Analysis

- Cooking Fuel

- Education

- 30/30 Online Presentations

- Competitions, Contests

- Earth Day 2021

- Earth Day 2022

- Earth Day 2023

- Earth Day 2024

- Earth Day 2025

- Executive Training

- Featured Study Programs

- Instagram TikTok Short Videos

- Internships

- Just a Minute

- K-12 Activities

- Mechanics training

- Online Courses

- Podcasts

- Scholarships/Fellowships

- Teacher Resources

- Technical Training

- Technician Training

- University/College Programs

- Events

- Coming Events

- Completed Events

- More Coming Events

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters

- Requests for Speakers, Presentations, Posters Completed

- Webinars/Online

- Webinars/Online Completed; often available on-demand

- Federal Agency/Executive Branch

- Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Agriculture (USDA)

- Commerce Department

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- Congressional Budget Office

- Defense (DOD)

- Air Force

- Army

- DARPA (Defense Advance Research Projects Agency)

- Defense Logistics Agency

- Marines

- Navy

- Education Department

- Energy (DOE)

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

- Federal Reserve System

- Federal Trade Commission

- Food and Drug Administration

- General Services Administration

- Government Accountability Office (GAO)

- Health and Human Services (HHS)

- Homeland Security

- Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

- Interior Department

- International Trade Commission

- Joint Office of Energy and Transportation

- Justice (DOJ)

- Labor Department

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- National Research Council

- National Science Foundation

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation

- Patent and Trademark Office

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- State Department

- Surface Transportation Board

- Transportation (DOT)

- Federal Aviation Administration

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)

- Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Admin (PHMSA)

- Treasury Department

- U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)

- White House

- Federal Legislation

- Federal Litigation

- Federal Regulation

- Feedstocks

- Agriculture/Food Processing Residues nonfield crop

- Alcohol/Ethanol/Isobutanol

- Algae/Other Aquatic Organisms/Seaweed

- Atmosphere

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

- Field/Orchard/Plantation Crops/Residues

- Forestry/Wood/Residues/Waste

- hydrogen

- Manure

- Methane/Biogas

- methanol/bio-/renewable methanol

- Not Agriculture

- RFNBO (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin)

- Seawater

- Sugars

- water

- Funding/Financing/Investing

- grants

- Green Jobs

- Green Racing

- Health Concerns/Benefits

- Heating Oil/Fuel

- History of Advanced Biofuels

- Infrastructure

- Aggregation

- Biofuels Engine Design

- Biorefinery/Fuel Production Infrastructure

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- certification

- Deliver Dispense

- Farming/Growing

- Precursors/Biointermediates

- Preprocessing

- Pretreatment

- Terminals Transport Pipelines

- International

- Abu Dhabi

- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Albania

- Algeria

- Angola

- Antarctica

- Arctic

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Aruba

- Asia

- Asia Pacific

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bahamas

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Barbados

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Belize

- Benin

- Bermuda

- Bhutan

- Bolivia

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Botswana

- Brazil

- Brunei

- Bulgaria

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Caribbean

- Central African Republic

- Central America

- Chad

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Congo

- Congo, Democratic Republic of

- Costa Rica

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Dubai

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eqypt

- Estonia

- Eswatini/Swaziland

- Ethiopia

- European Union (EU)

- Fiji

- Finland

- France

- French Guiana

- Gabon

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Global South

- Greece

- Greenland

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Guinea

- Guyana

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Ivory Coast

- Jamaica

- Japan

- Jersey

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Korea

- Kosovo

- Kuwait

- Laos

- Latin America

- Latvia

- Lebanon

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macedonia

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mali

- Malta

- Marshall Islands

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Mexico

- Middle East

- Moldova

- Monaco

- Mongolia

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Myanmar/Burma

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Netherlands

- New Guinea

- New Zealand

- Nicaragua

- Niger

- Nigeria

- North Africa

- North America

- North Korea

- Northern Ireland

- Norway

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Panama

- Papua New Guinea

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Republic of

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Scotland

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Sierra Leone

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South America

- South Korea

- South Sudan

- Southeast Asia

- Spain

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Suriname

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Timor-Leste

- Togo

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- UK (United Kingdom)

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates UAE

- Uruguay

- Uzbekistan

- Vatican

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Wales

- Zambia

- Zanzibar

- Zimbabwe

- Marine/Boat Bio and Renewable Fuel/MGO/MDO/SMF

- Marketing/Market Forces and Sales

- Opinions

- Organizations

- Original Writing, Opinions Advanced Biofuels USA

- Policy

- Presentations

- Biofuels Digest Conferences

- DOE Conferences

- Bioeconomy 2017

- Bioenergy2015

- Biomass2008

- Biomass2009

- Biomass2010

- Biomass2011

- Biomass2012

- Biomass2013

- Biomass2014

- DOE Project Peer Review

- Other Conferences/Events

- R & D Focus

- Carbon Capture/Storage/Use

- Co-Products

- Feedstock

- Logistics

- Performance

- Process

- Vehicle/Engine/Motor/Aircraft/Boiler

- Yeast

- Railroad/Train/Locomotive Fuel

- Resources

- Books Web Sites etc

- Business

- Definition of Advanced Biofuels

- Find Stuff

- Government Resources

- Scientific Resources

- Technical Resources

- Tools/Decision-Making

- Rocket/Missile Fuel

- Sponsors

- States

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawai'i

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Midwest

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Native American tribal nation lands

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington DC

- West Coast

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

- Sustainability

- Uncategorized

- What You Can Do

tags

© 2008-2023 Copyright Advanced BioFuels USA. All Rights reserved.

.jpg)

0 COMMENTS

Leave A Comment

Your Email Address wiil not be Published. Required Field Are marked*